Backyard Archaeology: Everyday things, attentive storying

Steve Brown

24 April 2024

‘Backyard Archaeology’: exhibition tile

What could be more everyday than the lost, abandoned, discarded, and decayed stuff that accumulates in a 20th century suburban backyard in Australia? After all, such things represent the forgotten plus unwanted material memories of daily life in an urban setting. In this blog, I use the example of my backyard explorations to argue for greater attention to be paid in heritage work to the routine and temporal aspects of everyday life.

Backyard Archaeology, Open Collections Gallery, Canberra Museum and Gallery. Image: Brenton McGeachie. Courtesy of CMAG

The exhibition ‘Backyard Archaeology’ (Canberra Museum + Gallery, 16 March – 1 September 2024) tells a story of collecting and digging across my home property in the suburb of Arncliffe, Sydney. Excavations of six test pits (covering an area of 5m2) resulted in the cataloguing of 3,600 artefacts, comprising remains of building materials, household leftovers (food debris, broken objects, packaging), personal adornment, and toys. The number of catalogued things indicate the presence of a quarter of a million things buried across the 347m2 property. That’s a lot of stuff!

I have published several articles on this project (see ‘Resources’ below), including on using mundane and everyday material culture to construct understandings of 20th century suburban experience, and on the ways found objects can inform feelings of place-attachment. This work is summarised in the guide to the Backyard Archaeology exhibition.

By way of situating my excavation work, in 2010 the NSW Government regulatory authority determined that I did not require an archaeological permit or exemption under the Heritage Act 1977 (NSW). The reason was that the place (or ‘site’) and potential findings being investigated were deemed not to meet a threshold of ‘local or State heritage significance’. While there is a degree of technical positioning to justify this determination, a consequence is that everyone is generally open to engage with everyday found objects in those local places where they live and that are not designated or authorised as heritage.

Such work can serve to strengthen identity and place-connectivity by creating a sense of inheritance from the past and an understanding of the diversity of everyday activity that has happened in any single place. While every place in Australia has an Indigenous history extending back up to 60,000 years, and this is an incredible matter to contemplate, here my focus is on the connections to stories of the 20th and early 21st centuries through (seemingly) ordinary things. As anthropologist Kathleen Stewart has stated so delightfully in her book Ordinary Affects (2007), ‘The ordinary is something that has to be imagined and inhabited’.

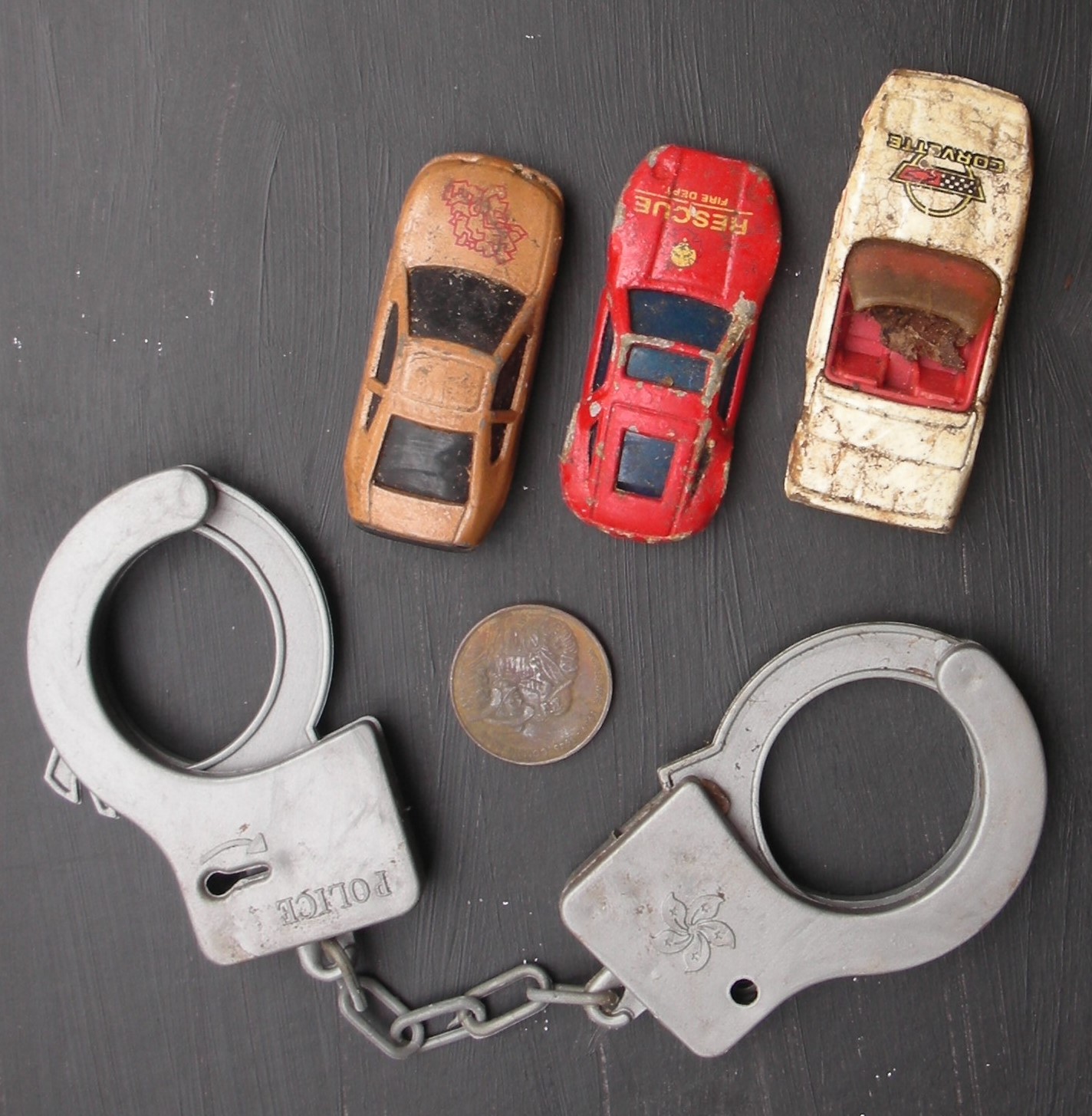

For example, in the Backyard Archaeology exhibition there is a group of objects recovered from the front roof-gutter of the Fairview Street cottage. The objects comprise three toy racing-cars, a set of plastic handcuffs with ‘POLICE’ embossed on each cuff, and a 20-cent coin commemorating the end of the Second World War.

I find this assemblage evocative. I imagine the fun and frivolity of children at play, away from the gaze of parents, as they challenge each other to lob ever-more toys into the gutter. However, the two Fairview Street boys who lived here before me were not just any children, but rather the two shy boys who had huddled beside their mother on a lounge room sofa when, in June 2007, I inspected the house. The gutter finds point to a boisterous and slightly naughty side to these children’s behaviour and personalities. The toys mark a sense of performing boyhoods in which miniature fast cars, money, and the long arm of the law appear as an innocent portrayal of adulthood – yet take place in the context of a house into which bullets were fired during a drive-by shooting in February 2006. A bullet hole that pierced the glass panel above the front door of the cottage, as well as the bullet recovered while gardening, are evidence of this event.

Whatever the reality of the boys’ lives and the story of the bullet hole, my attention to and material engagement with the toys and pierced glass panel drew out feelings and emotions that creatively, empathically, and imaginatively connected me with place, and even with my own childhood. I envisioned and sensed, but could never know, the lived-in, recent past.

The gutter assemblage is unlikely to be registered as official heritage, even though my speculations on the assemblage have been published and the objects are currently displayed in a museum exhibition. The objects illustrate the way in which the ordinary has become ‘imagined and inhabited’ and shows an everyday moment evoked by the often-overlooked stuff of everyday Australian suburban life. It’s not official heritage, but it is everyday heritage which has personal meaning – as well as a wider connection with a period in Sydney when drive-by shootings seemed commonplace.

Everyday heritage frequently resides outside of the official heritage system, yet provides a domain in which everyone, community member or heritage professional, can become engaged. That is, moments in past everyday lives can be informed by archaeology, history, creative practice, storying, place-making, and an attentiveness to the (seemingly) ordinary everyday activities of others.

Resources

Steve Brown (2024). Backyard Archaeology: Finding Things and Telling Stories. Available as a free download here.

Steve Brown (2012). Toward an archaeology of the twentieth-century suburban backyard. Archaeology in Oceania 47:99–106.

Steve Brown (2016). Experiencing place: an auto-ethnography on digging and belonging. Public History Review 23:9–24.

Steve Brown (2016). Practicing archaeology, placing things: toward an auto-ethnography of attachment. In A. Clarke and U. Frederick (eds), Contemporary Archaeology in Australia, pp.14–30. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholarly Press.

Steve Brown, Anne Clarke, Ursula Frederick (2015). Object Stories: Artifacts and Archaeologists. Left Coast Press; Taylor and Francis.